1988-02-29 Warren Buffett's Letters to Berkshire Shareholders

To the Shareholders of Berkshire Hathaway Inc.:

Our gain in net worth during 1987 was $464 million, or 19.5%. Over the last 23 years (that is, since present management took over), our per-share book value has grown from $19.46 to $2,477.47, or at a rate of 23.1% compounded annually.

1987年我们的净资产增加了4.64亿美元,增幅为19.5%。在过去23年(即现任管理层接手以来),我们的每股账面价值从19.46美元增长到2,477.47美元,年复合增长率为23.1%。

What counts, of course, is the rate of gain in per-share business value, not book value. In many cases, a corporation’s book value and business value are almost totally unrelated. For example, just before they went bankrupt, LTV and Baldwin-United published yearend audits showing their book values to be $652 million and $397 million, respectively. Conversely, Belridge Oil was sold to Shell in 1979 for $3.6 billion although its book value was only $177 million.

当然,真正重要的是每股企业价值的增长速度,而不是账面价值。在很多情况下,一家公司的账面价值与企业价值几乎完全无关。比如,LTV 和 Baldwin-United 在破产前不久公布的年终审计报告显示,它们的账面价值分别为6.52亿美元和3.97亿美元。相反,Belridge Oil 在1979年以36亿美元的价格卖给了 Shell,尽管它的账面价值只有1.77亿美元。

At Berkshire, however, the two valuations have tracked rather closely, with the growth rate in business value over the last decade moderately outpacing the growth rate in book value. This good news continued in 1987.

但在 Berkshire,这两种估值一直相当接近:过去十年里,企业价值的增长率略高于账面价值的增长率。这一好消息在1987年仍在延续。

Our premium of business value to book value has widened for two simple reasons: We own some remarkable businesses and they are run by even more remarkable managers.

我们的企业价值相对账面价值的溢价之所以扩大,有两个简单原因:我们拥有一些非同寻常的企业,而这些企业由更非同寻常的管理者在经营。

You have a right to question that second assertion. After all, CEOs seldom tell their shareholders that they have assembled a bunch of turkeys to run things. Their reluctance to do so makes for some strange annual reports. Oftentimes, in his shareholders’ letter, a CEO will go on for pages detailing corporate performance that is woefully inadequate. He will nonetheless end with a warm paragraph describing his managerial comrades as “our most precious asset.” Such comments sometimes make you wonder what the other assets can possibly be.

你完全有权质疑第二个断言。毕竟,CEO 很少会对股东说自己聚拢了一群“火鸡”来管事。他们不愿意这么说,反倒让一些年报变得颇为怪异。很多时候,CEO 会在致股东信里用好几页篇幅详细描述公司表现有多么令人失望;但他仍会在末尾用一段温情的话,把他的管理同僚称作“我们最宝贵的资产”。这种说法有时会让你忍不住想:那其他资产还能好到哪里去?

Right Business、Right People的顺序不能错了。

At Berkshire, however, my appraisal of our operating managers is, if anything, understated. To understand why, first take a look at page 7, where we show the earnings (on an historical-cost accounting basis) of our seven largest non-financial units: Buffalo News, Fechheimer, Kirby, Nebraska Furniture Mart, Scott Fetzer Manufacturing Group, See’s Candies, and World Book. In 1987, these seven business units had combined operating earnings before interest and taxes of $180 million.

但在 Berkshire,我对各经营单位经理的评价如果说有什么偏差,那也是偏保守。要理解为什么,请先看第7页:我们在那里列示了七家最大非金融业务单位——Buffalo News、Fechheimer、Kirby、Nebraska Furniture Mart、Scott Fetzer Manufacturing Group、See’s Candies、World Book——按历史成本会计口径计算的盈利情况。1987年,这七个业务单位合计实现了1.80亿美元的营业利润(扣除利息与税项之前)。

By itself, this figure says nothing about economic performance. To evaluate that, we must know how much total capital—debt and equity—was needed to produce these earnings. Debt plays an insignificant role at our seven units: Their net interest expense in 1987 was only $2 million. Thus, pre-tax earnings on the equity capital employed by these businesses amounted to $178 million. And this equity—again on an historical-cost basis—was only $175 million.

单看这个数字,本身并不能说明经济表现如何。要评估这一点,我们必须知道为了产生这些收益,一共投入了多少资本——包括债务与权益资本。在我们这七家单位里,债务几乎不起作用:1987年它们的净利息支出只有200万美元。因此,这些企业在所使用的权益资本上实现的税前利润为1.78亿美元。而这部分权益资本——同样按历史成本口径计算——只有1.75亿美元。

If these seven business units had operated as a single company, their 1987 after-tax earnings would have been approximately $100 million—a return of about 57% on equity capital. You’ll seldom see such a percentage anywhere, let alone at large, diversified companies with nominal leverage. Here’s a benchmark: In its 1988 Investor’s Guide issue, Fortune reported that among the 500 largest industrial companies and 500 largest service companies, only six had averaged a return on equity of over 30% during the previous decade. The best performer among the 1000 was Commerce Clearing House at 40.2%.

如果把这七个业务单位当作一家独立公司来看,它们1987年的税后收益大约会是1亿美元——相当于约57%的权益回报率。你几乎很难在任何地方见到这样的比例,更不用说是在名义杠杆极低的大型多元化公司中。这里给个基准:Fortune 在其1988年《Investor’s Guide》一期中报告称,在500家最大工业公司和500家最大服务公司中,只有6家在此前十年里平均权益回报率超过30%。而这1000家公司中表现最好的是 Commerce Clearing House,平均为40.2%。

Of course, the returns that Berkshire earns from these seven units are not as high as their underlying returns because, in aggregate, we bought the businesses at a substantial premium to underlying equity capital. Overall, these operations are carried on our books at about $222 million above the historical accounting values of the underlying assets. However, the managers of the units should be judged by the returns they achieve on the underlying assets; what we pay for a business does not affect the amount of capital its manager has to work with. (If, to become a shareholder and part owner of Commerce Clearing House, you pay, say, six times book value, that does not change CCH’s return on equity.)

当然,Berkshire 从这七家单位获得的回报并没有它们“底层”回报那么高,因为总体上我们以显著高于其底层权益资本的价格买入了这些企业。整体而言,这些经营实体在我们的账上所记录的价值,比其底层资产的历史会计价值高出约2.22亿美元。不过,对这些单位经理的评价,应当依据他们在底层资产上实现的回报;我们为企业支付的价格,并不会改变经理人能够运用的资本规模。(如果你为了成为 Commerce Clearing House 的股东、共同拥有者,支付了比如账面价值的六倍,这并不会改变 CCH 的权益回报率。)

Three important inferences can be drawn from the figures I have cited. First, the current business value of these seven units is far above their historical book value and also far above the value at which they are carried on Berkshire’s balance sheet. Second, because so little capital is required to run these businesses, they can grow while concurrently making almost all of their earnings available for deployment in new opportunities. Third, these businesses are run by truly extraordinary managers. The Blumkins, the Heldmans, Chuck Huggins, Stan Lipsey, and Ralph Schey all meld unusual talent, energy and character to achieve exceptional financial results.

从我引用的数据里,可以得出三条重要推论。第一,这七个单位的当前企业价值远高于它们的历史账面价值,也远高于它们在 Berkshire 资产负债表上的入账价值。第二,因为经营这些企业所需资本极少,它们可以在增长的同时,把几乎全部收益释放出来,用于配置到新的机会中。第三,这些企业由真正非凡的经理人经营。Blumkins 家族、Heldmans 家族、Chuck Huggins、Stan Lipsey、Ralph Schey,这些人把罕见的才干、能量与品格熔于一炉,取得了卓越的财务结果。

都是高产的果树,这些企业缺少吸纳新增资本的能力,但如果有这个能力也很难有高于平均水平的回报,于是最好的办法是配置到新的机会中。

For good reasons, we had very high expectations when we joined with these managers. In every case, however, our experience has greatly exceeded those expectations. We have received far more than we deserve, but we are willing to accept such inequities. (We subscribe to the view Jack Benny expressed upon receiving an acting award: “I don’t deserve this, but then, I have arthritis and I don’t deserve that either.”)

出于充分的理由,我们在与这些经理人合作之初就抱有很高的期待。但在每一种情况下,我们的实际体验都大大超出了那些期待。我们得到的回报远多于我们应得的,不过我们愿意接受这种“不公平”。(我们赞同 Jack Benny 在获得表演奖时表达的看法:“我不配得到这个,但我得了关节炎,我也不配得关节炎。”)

Beyond the Sainted Seven, we have our other major unit, insurance, which I believe also has a business value well above the net assets employed in it. However, appraising the business value of a property-casualty insurance company is a decidedly imprecise process. The industry is volatile, reported earnings oftentimes are seriously inaccurate, and recent changes in the Tax Code will severely hurt future profitability. Despite these problems, we like the business and it will almost certainly remain our largest operation. Under Mike Goldberg’s management, the insurance business should treat us well over time.

除了“被封圣的七家”之外,我们还有另一个主要单位——保险——我认为它的企业价值也显著高于投入其中的净资产。不过,评估一家财产与意外险公司的企业价值,是一个明显不精确的过程。这个行业波动很大,报告利润往往严重失真,而税法的近期变化将会严重伤害未来的盈利能力。尽管存在这些问题,我们仍然喜欢这门生意,它几乎肯定仍将是我们最大的业务。在 Mike Goldberg 的管理下,保险业务在长期应当会善待我们。

With managers like ours, my partner, Charlie Munger, and I have little to do with operations. in fact, it is probably fair to say that if we did more, less would be accomplished. We have no corporate meetings, no corporate budgets, and no performance reviews (though our managers, of course, oftentimes find such procedures useful at their operating units). After all, what can we tell the Blumkins about home furnishings, or the Heldmans about uniforms?

有了我们这样的经理人,我的合伙人 Charlie Munger 和我在运营层面几乎没什么事可做。事实上,可以说如果我们做得更多,反而完成得更少。我们没有公司层面的会议、没有公司层面的预算、也没有绩效评估(当然,我们的经理人有时会觉得这些程序在他们各自的经营单位里很有用)。毕竟,我们能告诉 Blumkins 家族什么是家居陈设?能告诉 Heldmans 家族什么是制服业务?

Our major contribution to the operations of our subsidiaries is applause. But it is not the indiscriminate applause of a Pollyanna. Rather it is informed applause based upon the two long careers we have spent intensively observing business performance and managerial behavior. Charlie and I have seen so much of the ordinary in business that we can truly appreciate a virtuoso performance. Only one response to the 1987 performance of our operating managers is appropriate: sustained, deafening applause.

我们对各子公司的运营所做的主要贡献,就是鼓掌。但这不是 Pollyanna 式的滥情鼓掌,而是“知情的鼓掌”——基于我们两人长期职业生涯中对经营表现与管理者行为的密集观察。Charlie 和我在商业世界里见过太多平庸,因此才能真正欣赏大师级的演出。对于我们经营经理人在1987年的表现,只有一种回应是恰当的:持续、震耳欲聋的掌声。

Sources of Reported Earnings

已报告收益的来源

The table on the following page shows the major sources of Berkshire’s reported earnings. In the table, amortization of Goodwill and other major purchase-price accounting adjustments are not charged against the specific businesses to which they apply but, instead, are aggregated and shown separately. In effect, this procedure presents the earnings of our businesses as they would have been reported had we not purchased them. In appendixes to my letters in the 1983 and 1986 annual reports, I explained why this form of presentation seems to us to be more useful to investors and managers than the standard GAAP presentation, which makes purchase-price adjustments on a business-by business basis. The total net earnings we show in the table are, of course, identical to the GAAP figures in our audited financial statements.

下一页的表格展示了 Berkshire 已报告收益的主要来源。在该表中,Goodwill 摊销以及其他重要的收购价会计调整,并不分摊计入其所对应的具体业务,而是汇总后单独列示。实际上,这种处理方式展示的是:如果我们从未收购这些企业,它们本来会被报告出来的盈利水平。我曾在1983年与1986年年报中致股东信的附录里解释过:为什么我们认为这种呈现方式,相比标准的 GAAP(按单个业务逐项确认收购价调整)更能帮助投资者与管理者理解真实经营情况。当然,我们在表中展示的净利润总额,与经审计财务报表中的 GAAP 数字完全一致。

In the Business Segment Data on pages 36-38 and in the Management’s Discussion section on pages 40-44 you will find much additional information about our businesses. In these sections you will also find our segment earnings reported on a GAAP basis. I urge you to read that material, as well as Charlie Munger’s letter to Wesco shareholders, describing the various businesses of that subsidiary, which starts on page 45.

在第36-38页的 Business Segment Data,以及第40-44页的 Management’s Discussion 中,你会找到关于我们各项业务的更多信息。在这些部分里,你也会看到按 GAAP 口径报告的分部收益。我建议你阅读这些材料,同时也阅读 Charlie Munger 写给 Wesco 股东、介绍该子公司各项业务的信件(从第45页开始)。

Gypsy Rose Lee announced on one of her later birthdays: “I have everything I had last year; it’s just that it’s all two inches lower.” As the table shows, during 1987 almost all of our businesses aged in a more upbeat way.

Gypsy Rose Lee 在她某个后期生日时宣布:“我拥有的还是和去年一样;只是它们都往下移了两英寸。”正如表格所显示的,我们在1987年的几乎所有业务,都以更令人振奋的方式“变老”。

There’s not a lot new to report about these businesses—and that’s good, not bad. Severe change and exceptional returns usually don’t mix. Most investors, of course, behave as if just the opposite were true. That is, they usually confer the highest price-earnings ratios on exotic-sounding businesses that hold out the promise of feverish change. That prospect lets investors fantasize about future profitability rather than face today’s business realities. For such investor-dreamers, any blind date is preferable to one with the girl next door, no matter how desirable she may be.

关于这些业务,并没有太多新东西可报告——这不是坏事,反而是好事。剧烈变化与卓越回报通常很难兼容。当然,大多数投资者的行为却好像恰恰相反:他们往往给那些听起来“异域”“新奇”的企业以最高的市盈率,因为这些企业承诺会发生令人发热的变化。这样的前景让投资者可以沉浸在对未来盈利的幻想中,而不必直面当下的商业现实。对这类“做梦的投资者”而言,任何一次盲约都胜过与隔壁那个女孩约会——不管她其实多么可取。

Experience, however, indicates that the best business returns are usually achieved by companies that are doing something quite similar today to what they were doing five or ten years ago. That is no argument for managerial complacency. Businesses always have opportunities to improve service, product lines, manufacturing techniques, and the like, and obviously these opportunities should be seized. But a business that constantly encounters major change also encounters many chances for major error. Furthermore, economic terrain that is forever shifting violently is ground on which it is difficult to build a fortress-like business franchise. Such a franchise is usually the key to sustained high returns.

但经验表明,最好的商业回报往往来自这样的公司:它们今天做的事,与五年或十年前做的事非常相似。这并不是在为管理层的自满开脱。企业总是有机会改进服务、产品线、制造技术等等,这些机会显然应当抓住。但一家企业如果持续遭遇重大变化,也就持续遭遇大量重大犯错的机会。更进一步说,在一个永远剧烈震荡、地形不断变化的经济环境里,很难建立起堡垒般的商业特许经营权(franchise)。而这种特许经营权,通常正是维持长期高回报的关键。

The Fortune study I mentioned earlier supports our view. Only 25 of the 1,000 companies met two tests of economic excellence—an average return on equity of over 20% in the ten years, 1977 through 1986, and no year worse than 15%. These business superstars were also stock market superstars: During the decade, 24 of the 25 outperformed the S&P 500.

我前面提到的 Fortune 研究支持了我们的观点。在1000家公司中,只有25家通过了两个“经济卓越”的测试:在1977到1986这十年间,平均权益回报率超过20%,并且任何一年都不低于15%。这些商业超级明星,在股市上也同样是超级明星:在那十年里,25家中的24家跑赢了标普500指数。

The Fortune champs may surprise you in two respects. First, most use very little leverage compared to their interest-paying capacity. Really good businesses usually don’t need to borrow. Second, except for one company that is “high-tech” and several others that manufacture ethical drugs, the companies are in businesses that, on balance, seem rather mundane. Most sell non-sexy products or services in much the same manner as they did ten years ago (though in larger quantities now, or at higher prices, or both). The record of these 25 companies confirms that making the most of an already strong business franchise, or concentrating on a single winning business theme, is what usually produces exceptional economics.

Fortune 的冠军公司可能会在两个方面让你感到意外。第一,它们相对于自身支付利息的能力,使用的杠杆普遍很低。真正优秀的企业通常不需要借钱。第二,除了一家“高科技”公司和几家生产处方药的公司之外,这些公司的业务整体看起来相当“朴素”。大多数公司卖的都是“不性感”的产品或服务,而且销售方式与十年前大体相同(只是如今卖得更多、价格更高,或两者兼有)。这25家公司的记录证明:把一个本来就很强的商业特许经营权发挥到极致,或专注于一个单一的制胜商业主题,通常才是产生卓越经济回报的路径。

少变化、少杠杆、长期高ROE。

Berkshire’s experience has been similar. Our managers have produced extraordinary results by doing rather ordinary things—but doing them exceptionally well. Our managers protect their franchises, they control costs, they search for new products and markets that build on their existing strengths and they don’t get diverted. They work exceptionally hard at the details of their businesses, and it shows.

Berkshire 的经验也相似。我们的经理人通过做相当普通的事,取得了非凡的结果——但他们把普通事做到了极致。我们的经理人保护自己的特许经营权,他们控制成本,他们寻找能够建立在既有优势之上的新产品与新市场,而且他们不被分心。他们在业务细节上付出了异常艰苦的努力,而成果清清楚楚地写在业绩里。

苹果,不进入自己没有优势的领域,这也是能力圈的定义。

Here’s an update:

下面是一次“更新”:

Agatha Christie, whose husband was an archaeologist, said that was the perfect profession for one’s spouse: “The older you become, the more interested they are in you.” It is students of business management, not archaeologists, who should be interested in Mrs. B (Rose Blumkin), the 94-year-old chairman of Nebraska Furniture Mart.

Agatha Christie(她的丈夫是考古学家)说,对配偶而言,考古学是完美的职业:“你越老,他们就越对你感兴趣。”真正应该对 B 太太(Rose Blumkin)感兴趣的,不是考古学家,而是商学院管理学的学生——她是 Nebraska Furniture Mart 的94岁董事长。

Fifty years ago Mrs. B started the business with $500, and today NFM is far and away the largest home furnishings store in the country. Mrs. B continues to work seven days a week at the job from the opening of each business day until the close. She buys, she sells, she manages—and she runs rings around the competition. It’s clear to me that she’s gathering speed and may well reach her full potential in another five or ten years. Therefore, I’ve persuaded the Board to scrap our mandatory retirement-at-100 policy. (And it’s about time: With every passing year, this policy has seemed sillier to me.)

五十年前,B 太太用500美元创办了这门生意;而今天,NFM 已经是全美遥遥领先的最大家居用品商店。B 太太至今仍一周七天工作:每天从开门一直干到关门。她采购、她销售、她管理——而且把竞争对手甩得团团转。在我看来,她显然还在“加速”,也许再过五到十年才能真正发挥全部潜力。因此,我已经说服董事会取消我们“满100岁强制退休”的政策。(也早该取消了:随着一年年过去,这条政策在我看来越来越像个蠢主意。)

Net sales of NFM were $142.6 million in 1987, up 8% from 1986. There’s nothing like this store in the country, and there’s nothing like the family Mrs. B has produced to carry on: Her son Louie, and his three boys, Ron, Irv and Steve, possess the business instincts, integrity and drive of Mrs. B. They work as a team and, strong as each is individually, the whole is far greater than the sum of the parts.

NFM 1987年的净销售额为1.426亿美元,比1986年增长8%。全国找不到第二家像它这样的商店,也找不到第二个像 B 太太培养出来、能接班延续的家族:她的儿子 Louie,以及 Louie 的三个儿子 Ron、Irv、Steve,都具备 B 太太那种商业直觉、正直品格与冲劲。他们团队协作;每个人单独看都很强,但合在一起的力量远大于部分之和。

The superb job done by the Blumkins benefits us as owners, but even more dramatically benefits NFM’s customers. They saved about $30 million in 1987 by buying from NFM. In other words, the goods they bought would have cost that much more if purchased elsewhere.

Blumkin 家族做出的卓越工作,让我们作为所有者受益,但更显著的受益者其实是 NFM 的顾客:1987年,顾客因为在 NFM 购买而节省了大约3,000万美元。换句话说,同样的商品如果在别处买,本该多花这么多钱。

You’ll enjoy an anonymous letter I received last August: “Sorry to see Berkshire profits fall in the second quarter. One way you may gain back part of your lost. (sic) Check the pricing at The Furniture Mart. You will find that they are leaving 10% to 20% on the table. This additional profit on $140 million of sells (sic) is $28 million. Not small change in anyone’s pocket! Check out other furniture, carpet, appliance and T.V. dealers. Your raising prices to a reasonable profit will help. Thank you. /signed/ A Competitor.”

你会喜欢我去年8月收到的一封匿名信:“很遗憾看到 Berkshire 第二季度利润下滑。你可以用一种办法把损失(sic)追回一部分:去检查一下 The Furniture Mart 的定价。你会发现他们把10%到20%的利润留在桌上没拿走。这在1.4亿美元的销售额(sells,sic)上,多出来的利润是2,800万美元。对任何人的口袋来说都不是小钱!去看看其他家具、地毯、家电和电视经销商。把价格提高到一个合理利润水平会有帮助。谢谢。/署名/ 一位竞争对手。”

NFM will continue to grow and prosper by following Mrs. B’s maxim: “Sell cheap and tell the truth.”

NFM 会继续成长并繁荣,因为它遵循 B 太太的座右铭:“卖得便宜,讲真话。”

Among dominant papers of its size or larger, the Buffalo News continues to be the national leader in two important ways: (1) its weekday and Sunday penetration rate (the percentage of households in the paper’s primary market area that purchase it); and (2) its “news-hole” percentage (the portion of the paper devoted to news).

在其规模相当或更大的强势报纸中,Buffalo News 在两个重要指标上依然是全美领头羊:(1) 工作日与周日的渗透率(即该报主要市场区域内购买报纸的家庭比例);(2) “news-hole”比例(即报纸版面中用于新闻内容的份额)。

每个生意都应该有自己的关键变量。

It may not be coincidence that one newspaper leads in both categories: an exceptionally “newsrich” product makes for broad audience appeal, which in turn leads to high penetration. Of course, quantity must be matched by quality. This not only means good reporting and good writing; it means freshness and relevance. To be indispensable, a paper must promptly tell its readers many things they want to know but won’t otherwise learn until much later, if ever.

一家报纸在两个指标上都领先,或许并非巧合:新闻内容异常“丰厚”的产品,会吸引更广泛的读者群,而这又会带来更高的渗透率。当然,数量必须匹配质量。这不仅意味着好的报道与好的写作;还意味着新鲜与相关。要做到不可或缺,一份报纸必须迅速告诉读者许多他们想知道、但否则要很久以后才会知道——甚至永远不会知道——的事情。

At the News, we put out seven fresh editions every 24 hours, each one extensively changed in content. Here’s a small example that may surprise you: We redo the obituary page in every edition of the News, or seven times a day. Any obituary added runs through the next six editions until the publishing cycle has been completed.

在 News,我们每24小时推出七个新鲜版本,每个版本在内容上都做了大幅更新。这里有个可能会让你吃惊的小例子:我们每一个版本都会重做讣告版——也就是一天七次。任何新增的讣告都会在接下来的六个版本里持续刊登,直到这一轮出版周期结束。

It’s vital, of course, for a newspaper to cover national and international news well and in depth. But it is also vital for it to do what only a local newspaper can: promptly and extensively chronicle the personally-important, otherwise-unreported details of community life. Doing this job well requires a very broad range of news—and that means lots of space, intelligently used.

当然,一份报纸把全国与国际新闻报道得好、报道得深,是至关重要的。但同样重要的是,它还必须做好只有本地报纸才能做的事:及时而充分地记录社区生活中那些对个人重要、却不会在其他地方被报道的细节。要把这件事做好,必须覆盖极其广泛的新闻范围——这就意味着需要大量版面,而且要聪明地使用这些版面。

Our news hole was about 50% in 1987, just as it has been year after year. If we were to cut it to a more typical 40%, we would save approximately $4 million annually in newsprint costs. That interests us not at all—and it won’t interest us even if, for one reason or another, our profit margins should significantly shrink.

我们1987年的“news hole”(新闻版面占比)大约是50%,一如既往、年复一年如此。如果我们把它削减到更典型的40%,每年大概能在新闻纸成本上节省约400万美元。这对我们毫无吸引力——即便将来因为某些原因,我们的利润率大幅收缩,这件事也依然不会让我们动心。

Charlie and I do not believe in flexible operating budgets, as in “Non-direct expenses can be X if revenues are Y, but must be reduced if revenues are Y—5%.” Should we really cut our news hole at the Buffalo News, or the quality of product and service at See’s, simply because profits are down during a given year or quarter? Or, conversely, should we add a staff economist, a corporate strategist, an institutional advertising campaign or something else that does Berkshire no good simply because the money currently is rolling in?

Charlie 和我不相信那种“弹性运营预算”,比如:“如果收入是Y,那么非直接费用可以是X;但如果收入变成Y—5%,费用就必须砍掉。”难道我们真的应该仅仅因为某一年或某个季度利润下滑,就去削减 Buffalo News 的新闻版面占比,或者降低 See’s 的产品与服务质量吗?反过来,仅仅因为眼下钱滚滚而来,我们就该增加一个员工经济学家、一个公司战略师、一场机构式广告宣传,或者其他对 Berkshire 毫无益处的东西吗?

That makes no sense to us. We neither understand the adding of unneeded people or activities because profits are booming, nor the cutting of essential people or activities because profitability is shrinking. That kind of yo-yo approach is neither business-like nor humane. Our goal is to do what makes sense for Berkshire’s customers and employees at all times, and never to add the unneeded. (“But what about the corporate jet?” you rudely ask. Well, occasionally a man must rise above principle.)

这在我们看来毫无道理。我们既不理解“因为利润大增就加上不需要的人和活动”,也不理解“因为盈利收缩就砍掉必要的人和活动”。那种溜溜球式的做法,既不商业,也不人道。我们的目标是:任何时候都只做对 Berkshire 的客户与员工有意义的事,永远不增加不需要的东西。(“那公司飞机呢?”你很粗鲁地问。好吧,偶尔,一个人也得超越原则。)

Although the News’ revenues have grown only moderately since 1984, superb management by Stan Lipsey, its publisher, has produced excellent profit growth. For several years, I have incorrectly predicted that profit margins at the News would fall. This year I will not let you down: Margins will, without question, shrink in 1988 and profit may fall as well. Skyrocketing newsprint costs will be the major cause.

尽管 News 的收入自1984年以来只算温和增长,但在其发行人 Stan Lipsey 的卓越管理下,利润增长却非常出色。过去好几年,我都错误地预测 News 的利润率会下滑。今年我不会让你失望:1988年利润率毫无疑问会收缩,利润也可能下降。新闻纸成本的飙升将是主要原因。

Fechheimer Bros. Company is another of our family businesses—and, like the Blumkins, what a family. Three generations of Heldmans have for decades consistently, built the sales and profits of this manufacturer and distributor of uniforms. In the year that Berkshire acquired its controlling interest in Fechheimer—1986—profits were a record. The Heldmans didn’t slow down after that. Last year earnings increased substantially and the outlook is good for 1988.

Fechheimer Bros. Company 也是我们的一家“家族企业”——而且和 Blumkin 家族一样,是个了不起的家族。Heldman 家族的三代人几十年来持续、稳定地提升这家制服制造与分销企业的销售与利润。Berkshire 在1986年取得 Fechheimer 的控股权益时,利润创下纪录。Heldman 家族在那之后并没有放慢脚步:去年利润大幅增长,1988年的前景也很好。

There’s nothing magic about the Uniform business; the only magic is in the Heldmans. Bob, George, Gary, Roger and Fred know the business inside and out, and they have fun running it. We are fortunate to be in partnership with them.

制服生意本身并没有什么魔法;唯一的魔法在 Heldman 家族身上。Bob、George、Gary、Roger、Fred 对这门生意了如指掌,而且他们经营起来乐在其中。能与他们成为合伙人,我们很幸运。

Chuck Huggins continues to set new records at See’s, just as he has ever since we put him in charge on the day of our purchase some 16 years ago. In 1987, volume hit a new high at slightly Under 25 million pounds. For the second year in a row, moreover, same-store sales, measured in pounds, were virtually unchanged. In case you are wondering, that represents improvement: In each of the previous six years, same-store sales had fallen.

Chuck Huggins 在 See’s 继续刷新纪录——自从我们大约16年前收购 See’s、并在收购当天就让他掌舵以来,他一直如此。1987年销量再创新高,略低于2,500万磅。并且,连续第二年,同店销量(按磅计)几乎没有变化。你如果觉得这不算进步,那我提醒你:在此前的六年里,同店销量每一年都在下降。

Although we had a particularly strong 1986 Christmas season, we racked up better store-for-store comparisons in the 1987 Christmas season than at any other time of the year. Thus, the seasonal factor at See’s becomes even more extreme. In 1987, about 85% of our profit was earned during December.

尽管我们在1986年的圣诞季表现特别强劲,但在1987年的圣诞季,我们拿到了全年里最好的同店对比表现。因此,See’s 的季节性因素变得更为极端。1987年,我们大约85%的利润是在12月赚到的。

Candy stores are fun to visit, but most have not been fun for their owners. From what we can learn, practically no one besides See’s has made significant profits in recent years from the operation of candy shops. Clearly, Chuck’s record at See’s is not due to a rising industry tide. Rather, it is a one-of-a-kind performance.

糖果店很适合逛——但对大多数老板来说,经营糖果店并不“好玩”。据我们所能了解的情况,近年来几乎没有谁能像 See’s 一样,通过经营糖果门店赚到可观利润。显然,Chuck 在 See’s 的成绩并不是因为行业大潮水涨船高;相反,这是独一无二的表现。

His achievement requires an excellent product—which we have—but it also requires genuine affection for the customer. Chuck is 100% customer-oriented, and his attitude sets the tone for the rest of the See’s organization.

他的成就需要优秀的产品——我们确实有——但还需要对顾客发自内心的喜爱。Chuck 是100%以顾客为中心的,他的态度也为整个 See’s 组织定下了基调。

Here’s an example of Chuck in action: At See’s we regularly add new pieces of candy to our mix and also cull a few to keep our product line at about 100 varieties. Last spring we selected 14 items for elimination. Two, it turned out, were badly missed by our customers, who wasted no time in letting us know what they thought of our judgment: “A pox on all in See’s who participated in the abominable decision…;” “May your new truffles melt in transit, may they sour in people’s mouths, may your costs go up and your profits go down…;” “We are investigating the possibility of obtaining a mandatory injunction requiring you to supply…;” You get the picture. In all, we received many hundreds of letters.

这里给你一个 Chuck “现场发挥”的例子:在 See’s,我们会定期往糖果组合里加入新品,同时也会淘汰一些品类,以便把产品线维持在大约100种口味/品类。去年春天,我们选定了14款准备淘汰。后来发现,其中两款被顾客严重想念。顾客们立刻用行动告诉我们,他们如何评价我们的判断:“愿所有参与这项可憎决定的 See’s 人都遭天谴……”;“愿你们的新松露在运输途中融化,愿它们在大家嘴里变酸,愿你们成本上升、利润下降……”;“我们正在研究是否能申请强制禁令,要求你们必须供应……”;你明白那种气氛了。总之,我们收到了好几百封来信。

Chuck not only reintroduced the pieces, he turned this miscue into an opportunity. Each person who had written got a complete and honest explanation in return. Said Chuck’s letter: “Fortunately, when I make poor decisions, good things often happen as a result…;” And with the letter went a special gift certificate.

Chuck 不仅把那两款糖果重新上架,还把这次“失手”变成了一个机会。每一位写信的人,都收到了我们完整而坦诚的解释。Chuck 在回信里写道:“幸运的是,当我做出糟糕决定时,往往也会因此发生好事……”;并且随信附上了一张特别的礼品券。

See’s increased prices only slightly in the last two years. In 1988 we have raised prices somewhat more, though still moderately. To date, sales have been weak and it may be difficult for See’s to improve its earnings this year.

过去两年里,See’s 只是小幅提价。1988年我们提价幅度稍大一些,但仍属温和。到目前为止,销售表现偏弱,因此 See’s 今年要提升盈利可能会有难度。

World Book, Kirby, and the Scott Fetzer Manufacturing Group are all under the management of Ralph Schey. And what a lucky thing for us that they are. I told you last year that Scott Fetzer performance in 1986 had far exceeded the expectations that Charlie and I had at the time of our purchase. Results in 1987 were even better. Pre-tax earnings rose 10% while average capital employed declined significantly.

World Book、Kirby、Scott Fetzer Manufacturing Group 都由 Ralph Schey 负责管理。它们归他管,对我们来说是多么幸运的事。我去年告诉过你,Scott Fetzer 在1986年的表现,远远超过了 Charlie 和我在收购时的预期。1987年的结果更好:税前利润增长10%,而平均占用资本却显著下降。

Ralph’s mastery of the 19 businesses for which he is responsible is truly amazing, and he has also attracted some outstanding managers to run them. We would love to find a few additional units that could be put under Ralph’s wing.

Ralph 对其负责的19项业务的驾驭能力,确实令人惊叹;同时,他也吸引了一批杰出的经理人来分别管理这些业务。我们很希望还能找到一些额外的单位,能够放到 Ralph 的“羽翼”之下。

The businesses of Scott Fetzer are too numerous to describe in detail. Let’s just update you on one of our favorites: At the end of 1987, World Book introduced its most dramatically-revised edition since 1962. The number of color photos was increased from 14,000 to 24,000; over 6,000 articles were revised; 840 new contributors were added. Charlie and I recommend this product to you and your family, as we do World Book’s products for younger children, Childcraft and Early World of Learning.

Scott Fetzer 的业务多到无法一一细述。我们只更新一下我们最喜欢的其中之一:在1987年末,World Book 推出了自1962年以来改版幅度最大的一版。彩色照片数量从14,000张增加到24,000张;超过6,000篇文章被修订;新增了840位撰稿人。Charlie 和我把这个产品推荐给你和你的家人——同样也推荐 World Book 面向更小孩子的产品:Childcraft 与 Early World of Learning。

In 1987, World Book unit sales in the United States increased for the fifth consecutive year. International sales and profits also grew substantially. The outlook is good for Scott Fetzer operations in aggregate, and for World Book in particular.

1987年,World Book 在美国的销量连续第五年增长。国际销售与利润也大幅增长。Scott Fetzer 的整体经营前景良好,而 World Book 尤其如此。

Insurance Operations

保险业务运营

Shown below is an updated version of our usual table presenting key figures for the insurance industry:

下方展示的是我们通常用于呈现保险行业关键指标的那张表格的更新版:

The combined ratio represents total insurance costs (losses incurred plus expenses) compared to revenue from premiums: A ratio below 100 indicates an underwriting profit, and one above 100 indicates a loss. When the investment income that an insurer earns from holding on to policyholders’ funds (“the float”) is taken into account, a combined ratio in the 107-111 range typically produces an overall break-even result, exclusive of earnings on the funds provided by shareholders.

综合成本率(combined ratio)表示保险总成本(已发生赔款加费用)相对于保费收入的比例:低于100意味着承保利润,高于100意味着承保亏损。再把保险公司因持有投保人资金(“the float”)而获得的投资收益考虑进去,综合成本率通常落在107-111区间时,整体结果大致会达到盈亏平衡——但这还不包括股东投入资金所带来的收益。

The math of the insurance business, encapsulated by the table, is not very complicated. In years when the industry’s annual gain in revenues (premiums) pokes along at 4% or 5%, underwriting losses are sure to mount. That is not because auto accidents, fires, windstorms and the like are occurring more frequently, nor has it lately been the fault of general inflation. Today, social and judicial inflation are the major culprits; the cost of entering a courtroom has simply ballooned. Part of the jump in cost arises from skyrocketing verdicts, and part from the tendency of judges and juries to expand the coverage of insurance policies beyond that contemplated by the insurer when the policies were written. Seeing no let-up in either trend, we continue to believe that the industry’s revenues must grow at about 10% annually for it to just hold its own in terms of profitability, even though general inflation may be running at a considerably lower rate.

保险生意的数学关系(表格已经把它浓缩了)并不复杂。当行业年度收入(保费)增幅只是在4%或5%附近“慢慢爬行”时,承保亏损必然会扩大。这不是因为车祸、火灾、风暴等发生得更频繁,也并非近来一般通胀的锅。今天,真正的元凶是“社会通胀”和“司法通胀”:走进法庭的成本已经膨胀到惊人程度。成本上升,一部分来自判决金额飙升,另一部分来自法官与陪审团倾向于把保单保障范围解释得比保险公司在出单时所设想的更宽。我们看不到这两股趋势有任何缓和,因此仍然认为:行业保费收入必须以大约每年10%的速度增长,才能在盈利能力上“勉强站稳”,即便一般通胀率可能显著更低。

保险离推动通胀的源头很近,包括医疗保险,但医保没有浮存金。

The strong revenue gains of 1985-87 almost guaranteed the industry an excellent underwriting performance in 1987 and, indeed, it was a banner year. But the news soured as the quarters rolled by: Best’s estimates that year-over-year volume increases were 12.9%, 11.1%, 5.7%, and 5.6%. In 1988, the revenue gain is certain to be far below our 10% “equilibrium” figure. Clearly, the party is over.

1985-87年的强劲保费增长几乎保证了行业在1987年取得出色的承保表现——事实也确实如此,那是一个“丰收年”。但随着季度推进,消息逐渐变味:Best’s 估算的同比保费增幅分别是12.9%、11.1%、5.7%、5.6%。到了1988年,保费增幅肯定会远低于我们所说的10%“均衡”水平。很明显,派对结束了。

However, earnings will not immediately sink. A lag factor exists in this industry: Because most policies are written for a one-year term, higher or lower insurance prices do not have their full impact on earnings until many months after they go into effect. Thus, to resume our metaphor, when the party ends and the bar is closed, you are allowed to finish your drink. If results are not hurt by a major natural catastrophe, we predict a small climb for the industry’s combined ratio in 1988, followed by several years of larger increases.

不过,盈利不会立刻下沉。这个行业存在滞后效应:大多数保单期限是一年,因此保险价格的上调或下调,要过许多个月才会对盈利产生完全影响。借用我们的比喻:派对结束、酒吧打烊后,你仍被允许把杯中的酒喝完。如果没有重大自然灾害冲击业绩,我们预测行业综合成本率在1988年会小幅上升,随后几年会出现更大幅度的上升。

The insurance industry is cursed with a set of dismal economic characteristics that make for a poor long-term outlook: hundreds of competitors, ease of entry, and a product that cannot be differentiated in any meaningful way. In such a commodity-like business, only a very low-cost operator or someone operating in a protected, and usually small, niche can sustain high profitability levels.

保险行业被一组糟糕的经济特性“诅咒”,因此长期前景不佳:竞争者成百上千、进入门槛低、产品在任何有意义的维度上都难以差异化。在这种近似大宗商品的生意里,只有极低成本的经营者,或在受保护(且通常很小)的细分利基中经营的人,才能维持高水平的盈利。

BRK是先做投资,再转入控股,再转入保险,通过保险最大化最终的净资产。

When shortages exist, however, even commodity businesses flourish. The insurance industry enjoyed that kind of climate for a while but it is now gone. One of the ironies of capitalism is that most managers in commodity industries abhor shortage conditions—even though those are the only circumstances permitting them good returns. Whenever shortages appear, the typical manager simply can’t wait to expand capacity and thereby plug the hole through which money is showering upon him. This is precisely what insurance managers did in 1985-87, confirming again Disraeli’s observation: “What we learn from history is that we do not learn from history.”

然而,一旦出现“供给短缺”,即便是大宗商品式的行业也会繁荣。保险业曾享受过一段这样的气候,但现在它已消失。资本主义的一大讽刺在于:大宗商品行业的大多数管理者厌恶短缺环境——尽管恰恰只有在短缺时,他们才可能获得好回报。每当短缺出现,典型经理人就迫不及待扩张产能,去堵住那个“金钱正从中倾泻而下”的洞。1985-87年保险业的管理者正是这么干的,再一次印证了 Disraeli 的那句观察:“我们从历史中学到的,是我们不会从历史中学习。”

At Berkshire, we work to escape the industry’s commodity economics in two ways. First, we differentiate our product by our financial strength, which exceeds that of all others in the industry. This strength, however, is limited in its usefulness. It means nothing in the personal insurance field: The buyer of an auto or homeowners policy is going to get his claim paid even if his insurer fails (as many have). It often means nothing in the commercial insurance arena: When times are good, many major corporate purchasers of insurance and their brokers pay scant attention to the insurer’s ability to perform under the more adverse conditions that may exist, say, five years later when a complicated claim is finally resolved. (Out of sight, out of mind—and, later on, maybe out-of-pocket.)

在 Berkshire,我们通过两种方式努力逃离行业这种“商品化”的经济学。第一,我们用财务实力来差异化我们的产品,而我们的财务实力超过业内任何其他公司。不过,这种优势的用途也有限:在个人保险领域它毫无意义——买车险或房主险的人,即便保险公司倒闭(这种事发生过很多),也照样会拿到赔款。在商业保险领域,它也常常毫无意义:当环境好时,许多大型企业买家及其经纪人很少关注保险公司在更不利条件下的履约能力——比如五年后,一桩复杂索赔终于要结案时。(眼不见心不烦——然后可能就要自己掏腰包。)

Periodically, however, buyers remember Ben Franklin’s observation that it is hard for an empty sack to stand upright and recognize their need to buy promises only from insurers that have enduring financial strength. It is then that we have a major competitive advantage. When a buyer really focuses on whether a $10 million claim can be easily paid by his insurer five or ten years down the road, and when he takes into account the possibility that poor underwriting conditions may then coincide with depressed financial markets and defaults by reinsurer, he will find only a few companies he can trust. Among those, Berkshire will lead the pack.

然而,买方也会周期性地想起 Ben Franklin 的那句观察:空麻袋很难站直——于是他们意识到,自己只能向那些拥有持久财务实力的保险公司购买“承诺”。正是在这种时候,我们就拥有了重大的竞争优势。当买方真正聚焦于:五年或十年后,一笔1,000万美元的索赔,保险公司是否能轻松支付;并且把这样一种可能性也纳入考虑——糟糕的承保环境也许会与低迷的金融市场、以及再保险人违约同时出现——他就会发现:他能信任的公司只有少数几家。而在这些公司里,Berkshire 会领跑。

Our second method of differentiating ourselves is the total indifference to volume that we maintain. In 1989, we will be perfectly willing to write five times as much business as we write in 1988—or only one-fifth as much. We hope, of course, that conditions will allow us large volume. But we cannot control market prices. If they are unsatisfactory, we will simply do very little business. No other major insurer acts with equal restraint.

我们差异化自己的第二种方式,是我们对业务规模(volume)保持彻底的无所谓。1989年,我们完全愿意把业务量做成1988年的五倍——也同样愿意只做1988年的五分之一。当然,我们希望条件允许我们做大规模;但我们无法控制市场价格。如果价格不令人满意,我们就干脆几乎不做业务。没有任何一家主要保险公司能像我们这样克制。

两种方式都指向投资,用投资能力实现差异化。

Three conditions that prevail in insurance, but not in most businesses, allow us our flexibility. First, market share is not an important determinant of profitability: In this business, in contrast to the newspaper or grocery businesses, the economic rule is not survival of the fattest. Second, in many sectors of insurance, including most of those in which we operate, distribution channels are not proprietary and can be easily entered: Small volume this year does not preclude huge volume next year. Third, idle capacity—which in this industry largely means people—does not result in intolerable costs. In a way that industries such as printing or steel cannot, we can operate at quarter-speed much of the time and still enjoy long-term prosperity.

保险业里存在三条条件——多数行业并不具备——使我们可以拥有这种灵活性。第一,市场份额并不是盈利能力的重要决定因素:在这个行业里,与报纸或杂货行业不同,经济规律不是“胖者生存”。第二,在保险的许多领域(包括我们经营的大多数领域),分销渠道并非专属,进入也很容易:今年量小,并不妨碍明年量巨大。第三,闲置产能——在这个行业里主要意味着“人”——不会带来难以忍受的成本。与印刷或钢铁等行业不同,我们可以在很长时间里以四分之一速度运转,却仍能享有长期繁荣。

We follow a price-based-on-exposure, not-on-competition policy because it makes sense for our shareholders. But we’re happy to report that it is also pro-social. This policy means that we are always available, given prices that we believe are adequate, to write huge volumes of almost any type of property-casualty insurance. Many other insurers follow an in-and-out approach. When they are “out”—because of mounting losses, capital inadequacy, or whatever—we are available. Of course, when others are panting to do business we are also available—but at such times we often find ourselves priced above the market. In effect, we supply insurance buyers and brokers with a large reservoir of standby capacity.

我们奉行“按风险暴露定价、而不是按竞争对手定价”的政策,因为这对股东有利。但我们也很高兴地报告:这同样具有“亲社会”的效果。这个政策意味着:只要价格达到我们认为足够的水平,我们随时可以承接几乎任何类型的财产与意外险的大规模业务。许多其他保险公司采取“进进出出”的做法:当他们“退出”——因为亏损攀升、资本不足或其他原因——我们依然在场可用。当然,当别人气喘吁吁想抢生意时,我们也在场——只不过那种时候我们往往发现自己报的价格高于市场。实际上,我们为保险买方与经纪人提供了一个巨大的“备用承保能力水库”。

One story from mid-1987 illustrates some consequences of our pricing policy: One of the largest family-owned insurance brokers in the country is headed by a fellow who has long been a shareholder of Berkshire. This man handles a number of large risks that are candidates for placement with our New York office. Naturally, he does the best he can for his clients. And, just as naturally, when the insurance market softened dramatically in 1987 he found prices at other insurers lower than we were willing to offer. His reaction was, first, to place all of his business elsewhere and, second, to buy more stock in Berkshire. Had we been really competitive, he said, we would have gotten his insurance business but he would not have bought our stock.

1987年年中发生的一件事,能说明我们的定价政策会带来哪些后果:美国最大的家族控股保险经纪公司之一,由一位长期持有 Berkshire 股票的人领导。他经手许多大型风险,这些都是我们纽约办公室可能承接的业务。很自然,他会尽最大努力为客户争取最优条件;也同样自然地,当1987年保险市场显著软化时,他在其他保险公司那里看到了比我们愿意给出的更低价格。他的反应是:第一,把所有业务都放到别家;第二,买入更多 Berkshire 股票。他说,如果我们真的那么有竞争力,我们会拿到他的保险业务,但他就不会买我们的股票了。

Berkshire’s underwriting experience was excellent in 1987, in part because of the lag factor discussed earlier. Our combined ratio (on a statutory basis and excluding structured settlements and financial reinsurance) was 105. Although the ratio was somewhat less favorable than in 1986, when it was 103, our profitability improved materially in 1987 because we had the use of far more float. This trend will continue to run in our favor: Our ratio of float to premium volume will increase very significantly during the next few years. Thus, Berkshire’s insurance profits are quite likely to improve during 1988 and 1989, even though we expect our combined ratio to rise.

Berkshire 在1987年的承保经历非常出色,部分原因来自前面讨论过的滞后效应。我们的综合成本率(按法定口径,并剔除结构化赔付与金融再保险)为105。虽然这一比率不如1986年(当时为103)那么理想,但我们1987年的盈利能力却明显改善,因为我们可运用的 float 大得多。这个趋势会继续对我们有利:未来几年里,我们的“float 相对于保费规模”的比例将显著上升。因此,即便我们预计综合成本率会上升,Berkshire 的保险利润在1988年与1989年仍很可能继续改善。

Our insurance business has also made some important non-financial gains during the last few years. Mike Goldberg, its manager, has assembled a group of talented professionals to write larger risks and unusual coverages. His operation is now well equipped to handle the lines of business that will occasionally offer us major opportunities.

过去几年里,我们的保险业务也取得了一些重要的非财务进展。其负责人 Mike Goldberg 组建了一支有才干的专业团队,能够承接更大额度的风险与更不寻常的保障责任。现在,他的团队已经具备了处理那些偶尔会为我们带来重大机会的业务线的能力。

Our loss reserve development, detailed on pages 41-42, looks better this year than it has previously. But we write lots of “long-tail” business—that is, policies generating claims that often take many years to resolve. Examples would be product liability, or directors and officers liability coverages. With a business mix like this, one year of reserve development tells you very little.

我们在第41-42页详细披露的准备金变动(loss reserve development),今年看起来比以往更好。但我们承保了大量“长尾”业务——也就是会产生索赔、而这些索赔往往需要很多年才能最终结案的保单。例如产品责任险、董监高责任险(directors and officers liability)等。在这样的业务结构下,一年期的准备金变动信息几乎说明不了什么。

You should be very suspicious of any earnings figures reported by insurers (including our own, as we have unfortunately proved to you in the past). The record of the last decade shows that a great many of our best-known insurers have reported earnings to shareholders that later proved to be wildly erroneous. In most cases, these errors were totally innocent: The unpredictability of our legal system makes it impossible for even the most conscientious insurer to come close to judging the eventual cost of long-tail claims.

你应当对保险公司(包括我们自己——我们过去不幸已经向你证明过这一点)所报告的任何盈利数字都保持高度怀疑。过去十年的记录表明,许多最知名的保险公司曾向股东报告盈利,但后来证明这些数字错得离谱。在大多数情况下,这些错误完全是无心的:法律体系的不可预测性,使得即便最尽责的保险公司,也不可能接近准确判断长尾索赔的最终成本。

Nevertheless, auditors annually certify the numbers given them by management and in their opinions unqualifiedly state that these figures “present fairly” the financial position of their clients. The auditors use this reassuring language even though they know from long and painful experience that the numbers so certified are likely to differ dramatically from the true earnings of the period. Despite this history of error, investors understandably rely upon auditors’ opinions. After all, a declaration saying that “the statements present fairly” hardly sounds equivocal to the non-accountant.

尽管如此,审计师每年仍会对管理层提供的数字进行认证,并在审计意见中毫无保留地写道:这些数字“公允反映(present fairly)”了客户的财务状况。审计师使用这种让人安心的措辞,即便他们从漫长而痛苦的经验中知道:被认证的数字很可能与该期间的真实盈利存在巨大差异。尽管这种错误历史客观存在,投资者仍然可以理解地依赖审计意见——毕竟,对非会计专业人士来说,“报表公允反映”这句话听上去一点都不含糊。

The wording in the auditor’s standard opinion letter is scheduled to change next year. The new language represents improvement, but falls far short of describing the limitations of a casualty-insurer audit. If it is to depict the true state of affairs, we believe the standard opinion letter to shareholders of a property-casualty company should read something like: “We have relied upon representations of management in respect to the liabilities shown for losses and loss adjustment expenses, the estimate of which, in turn, very materially affects the earnings and financial condition herein reported. We can express no opinion about the accuracy of these figures. Subject to that important reservation, in our opinion, etc.”

审计师标准意见函中的措辞,计划在明年做出修改。新的语言算是一种改进,但距离准确描述财产意外险审计的局限性仍差得很远。若要真正反映事实,我们认为一家财产意外险公司的“给股东的标准意见函”应当写得更像这样:“关于报表中列示的赔付及理赔费用准备金,我们依赖管理层的陈述;而这些准备金的估计又会对本文所报告的盈利与财务状况产生极其重大的影响。我们无法就这些数字的准确性发表任何意见。基于这一重要保留前提,我们认为……等等。”

If lawsuits develop in respect to wildly inaccurate financial statements (which they do), auditors will definitely say something of that sort in court anyway. Why should they not be forthright about their role and its limitations from the outset?

如果因严重失真的财务报表而引发诉讼(确实会发生),审计师在法庭上反正也一定会这么说。那他们为什么不从一开始就对自己的角色及其局限性坦率一点?

We want to emphasize that we are not faulting auditors for their inability to accurately assess loss reserves (and therefore earnings). We fault them only for failing to publicly acknowledge that they can’t do this job.

我们要强调:我们并不是责怪审计师无法准确评估赔付准备金(因此也无法准确评估盈利)。我们只责怪他们没有在公开场合承认:这件事他们做不到。

From all appearances, the innocent mistakes that are constantly made in reserving are accompanied by others that are deliberate. Various charlatans have enriched themselves at the expense of the investing public by exploiting, first, the inability of auditors to evaluate reserve figures and, second, the auditors’ willingness to confidently certify those figures as if they had the expertise to do so. We will continue to see such chicanery in the future. Where “earnings” can be created by the stroke of a pen, the dishonest will gather. For them, long-tail insurance is heaven. The audit wording we suggest would at least serve to put investors on guard against these predators.

从各方面看,在准备金计提上不断出现的“无心之失”,还伴随着一些“蓄意为之”的把戏。某些江湖骗子通过两点漏洞——第一,审计师无法评估准备金数字;第二,审计师又愿意把这些数字以一种自信满满的姿态认证,好像自己具备相应专长——在投资公众的代价上让自己大发其财。将来我们还会继续看到这种欺诈。只要“盈利”可以靠一支笔一划就被“创造”出来,不诚实的人就会聚集。对他们而言,长尾保险就是天堂。我们建议的审计措辞,至少能起到提醒投资者提防这些掠食者的作用。

The taxes that insurance companies pay—which increased materially, though on a delayed basis, upon enactment of the Tax Reform Act of 1986—took a further turn for the worse at the end of 1987. We detailed the 1986 changes in last year’s report. We also commented on the irony of a statute that substantially increased 1987 reported earnings for insurers even as it materially reduced both their long-term earnings potential and their business value. At Berkshire, the temporarily-helpful “fresh start” adjustment inflated 1987 earnings by $8.2 million.

保险公司所缴纳的税——在《1986年税改法案》通过后虽有滞后、但仍显著上升——在1987年末又进一步恶化。我们在去年的报告中详细说明了1986年的变化。我们也评论过一个讽刺之处:这部法律在显著降低保险公司长期盈利潜力与企业价值的同时,却又显著抬高了1987年的“报告盈利”。在 Berkshire,那个短期有利的“fresh start(重新起步)”调整,使1987年盈利被抬高了820万美元。

In our opinion, the 1986 Act was the most important economic event affecting the insurance industry over the past decade. The 1987 Bill further reduced the intercorporate dividends-received credit from 80% to 70%, effective January 1, 1988, except for cases in which the taxpayer owns at least 20% of an investee.

在我们看来,1986年法案是过去十年里影响保险行业最重要的经济事件。1987年的法案进一步把公司间股息的“已纳税股息扣除”(dividends-received credit)从80%降到70%,自1988年1月1日起生效——但纳税人对被投资企业持股至少20%的情形除外。

Investors who have owned stocks or bonds through corporate intermediaries other than qualified investment companies have always been disadvantaged in comparison to those owning the same securities directly. The penalty applying to indirect ownership was greatly increased by the 1986 Tax Bill and, to a lesser extent, by the 1987 Bill, particularly in instances where the intermediary is an insurance company. We have no way of offsetting this increased level of taxation. It simply means that a given set of pre-tax investment returns will now translate into much poorer after-tax results for our shareholders.

那些通过(不符合资格的)公司中介而间接持有股票或债券的投资者,相比于直接持有同样证券的人,一直处于劣势。(“公司中介”不包括合格的投资公司。)1986年税改大幅加重了这种对间接持有的惩罚;1987年法案在较小程度上进一步加重了惩罚,尤其当中介是保险公司时更为明显。我们没有办法抵消这一级别更高的税负。这意味着,同一组税前投资回报,现在会给我们的股东带来更差得多的税后结果。

All in all, we expect to do well in the insurance business, though our record is sure to be uneven. The immediate outlook is for substantially lower volume but reasonable earnings improvement. The decline in premium volume will accelerate after our quota-share agreement with Fireman’s Fund expires in 1989. At some point, likely to be at least a few years away, we may see some major opportunities, for which we are now much better prepared than we were in 1985.

总的来说,我们预计保险业务会做得不错,尽管我们的业绩记录注定会起起伏伏。眼前的展望是:保费规模将显著下降,但盈利有望出现合理改善。随着我们与 Fireman’s Fund 的 quota-share(配额分保)协议在1989年到期,保费规模的下降还会加速。未来某个时点——很可能至少还要几年——我们也许会看到一些重大机会;而为这些机会,我们现在的准备程度,已经远好于1985年。

Marketable Securities—Permanent Holdings

可流通证券——永久持有

Whenever Charlie and I buy common stocks for Berkshire’s insurance companies (leaving aside arbitrage purchases, discussed later) we approach the transaction as if we were buying into a private business. We look at the economic prospects of the business, the people in charge of running it, and the price we must pay. We do not have in mind any time or price for sale. Indeed, we are willing to hold a stock indefinitely so long as we expect the business to increase in intrinsic value at a satisfactory rate. When investing, we view ourselves as business analysts—not as market analysts, not as macroeconomic analysts, and not even as security analysts.

每当 Charlie 和我为 Berkshire 的保险公司买入普通股(先把后面要谈的套利买入放在一边),我们都会把这笔交易当成是在“买入一家私人企业的一部分”。我们看的是企业的经济前景、负责经营它的人、以及我们必须支付的价格。我们心里并没有任何预设的卖出时间或卖出价格。事实上,只要我们预计这家企业的内在价值会以令人满意的速度增长,我们就愿意无限期持有这只股票。投资时,我们把自己视为企业分析师——不是市场分析师,不是宏观经济分析师,甚至也不是证券分析师。

Our approach makes an active trading market useful, since it periodically presents us with mouth-watering opportunities. But by no means is it essential: a prolonged suspension of trading in the securities we hold would not bother us any more than does the lack of daily quotations on World Book or Fechheimer. Eventually, our economic fate will be determined by the economic fate of the business we own, whether our ownership is partial or total.

这种方法使得活跃的交易市场很有用,因为它会周期性地给我们端上“令人垂涎”的机会。但它绝非必需:即便我们持有的证券长期停牌,也不会比 World Book 或 Fechheimer 没有每日报价更让我们在意。最终,我们的经济命运取决于我们所拥有企业的经济命运——不管这种所有权是部分的还是完全的。

Ben Graham, my friend and teacher, long ago described the mental attitude toward market fluctuations that I believe to be most conducive to investment success. He said that you should imagine market quotations as coming from a remarkably accommodating fellow named Mr. Market who is your partner in a private business. Without fail, Mr. Market appears daily and names a price at which he will either buy your interest or sell you his.

我的朋友兼老师 Ben Graham 很早以前就描述过一种他认为最有利于投资成功的、面对市场波动时应有的心理态度。他说,你应该把市场报价想象成来自一个非常“乐于配合”的人,名叫 Mr. Market——他是你在一家私人企业里的合伙人。Mr. Market 每天都会出现,报出一个价格:在这个价格上,他要么买下你持有的份额,要么把他的份额卖给你。

Even though the business that the two of you own may have economic characteristics that are stable, Mr. Market’s quotations will be anything but. For, sad to say, the poor fellow has incurable emotional problems. At times he feels euphoric and can see only the favorable factors affecting the business. When in that mood, he names a very high buy-sell price because he fears that you will snap up his interest and rob him of imminent gains. At other times he is depressed and can see nothing but trouble ahead for both the business and the world. On these occasions he will name a very low price, since he is terrified that you will unload your interest on him.

即便你们俩共同拥有的那门生意,其经济特性可能非常稳定,Mr. Market 的报价却绝不会稳定。因为很遗憾,这位可怜的家伙有无法治愈的情绪问题。有时他兴高采烈,只看得到影响企业的有利因素。处在这种情绪下,他会报出很高的买卖价格,因为他害怕你会一把抢走他的份额,让他错失眼前的收益。另一些时候,他又陷入沮丧,只看得到企业与世界的各种麻烦。在这些时候,他会报出很低的价格,因为他恐惧你会把你的份额甩给他。

Mr. Market has another endearing characteristic: He doesn’t mind being ignored. If his quotation is uninteresting to you today, he will be back with a new one tomorrow. Transactions are strictly at your option. Under these conditions, the more manic-depressive his behavior, the better for you.

Mr. Market 还有一个可爱的特点:他不介意被你忽略。如果他今天的报价对你没意思,明天他会带着一个新报价再来。一切交易完全由你决定。在这种条件下,他的躁狂—抑郁越严重,对你越有利。

But, like Cinderella at the ball, you must heed one warning or everything will turn into pumpkins and mice: Mr. Market is there to serve you, not to guide you. It is his pocketbook, not his wisdom, that you will find useful. If he shows up some day in a particularly foolish mood, you are free to either ignore him or to take advantage of him, but it will be disastrous if you fall under his influence. Indeed, if you aren’t certain that you understand and can value your business far better than Mr. Market, you don’t belong in the game. As they say in poker, “If you’ve been in the game 30 minutes and you don’t know who the patsy is, you’re the patsy.”

但是,就像舞会上 Cinderella 一样,你必须记住一个警告,否则一切都会变成南瓜和老鼠:Mr. Market 是来为你服务的,不是来指挥你的。对你有用的是他的口袋,而不是他的智慧。某一天如果他带着特别愚蠢的情绪出现,你尽可以忽略他,或者利用他;但如果你被他的情绪所左右,那将是灾难性的。确实如此:如果你不能确定自己对企业的理解与估值能力远胜于 Mr. Market,你就不该参与这场游戏。就像扑克里常说的:“如果你坐在牌桌上30分钟还不知道谁是冤大头(patsy),那你就是冤大头。”

Ben’s Mr. Market allegory may seem out-of-date in today’s investment world, in which most professionals and academicians talk of efficient markets, dynamic hedging and betas. Their interest in such matters is understandable, since techniques shrouded in mystery clearly have value to the purveyor of investment advice. After all, what witch doctor has ever achieved fame and fortune by simply advising “Take two aspirins”?

Ben 的 Mr. Market 寓言在今天的投资世界里,可能看起来有点过时——在这个世界里,大多数职业人士与学者谈论的是有效市场、动态对冲与贝塔。人们对这些话题感兴趣是可以理解的:对投资建议的兜售者而言,那些被神秘感包裹的技术显然更“有卖点”。毕竟,有哪个巫医能靠一句“吃两片阿司匹林”就名利双收?

The value of market esoterica to the consumer of investment advice is a different story. In my opinion, investment success will not be produced by arcane formulae, computer programs or signals flashed by the price behavior of stocks and markets. Rather an investor will succeed by coupling good business judgment with an ability to insulate his thoughts and behavior from the super-contagious emotions that swirl about the marketplace. In my own efforts to stay insulated, I have found it highly useful to keep Ben’s Mr. Market concept firmly in mind.

但这些市场玄学对投资建议消费者的价值,就另当别论了。在我看来,投资成功不会来自晦涩公式、计算机程序,或股票与市场价格行为所闪烁出的信号。相反,投资者成功的关键在于:把良好的商业判断,与一种能够让自己的思想与行为不被市场上高度传染性的情绪所裹挟的能力结合起来。为了让自己保持这种“隔离”,我发现把 Ben 的 Mr. Market 概念牢牢记在心里非常有用。

Following Ben’s teachings, Charlie and I let our marketable equities tell us by their operating results—not by their daily, or even yearly, price quotations—whether our investments are successful. The market may ignore business success for a while, but eventually will confirm it. As Ben said: “In the short run, the market is a voting machine but in the long run it is a weighing machine.” The speed at which a business’s success is recognized, furthermore, is not that important as long as the company’s intrinsic value is increasing at a satisfactory rate. In fact, delayed recognition can be an advantage: It may give us the chance to buy more of a good thing at a bargain price.

遵循 Ben 的教导,Charlie 和我让我们持有的可交易权益资产用“经营结果”来告诉我们投资是否成功——而不是用每天、甚至每年的价格报价来评判。市场也许会暂时忽视企业的经营成功,但最终会确认它。正如 Ben 所说:“短期里,市场是一台投票机;长期里,市场是一台称重机。”此外,企业的成功被市场承认得快还是慢,并不那么重要,只要企业的内在价值正在以令人满意的速度增长。事实上,承认来得晚反而可能是优势:它可能给我们机会,以便宜价格买到更多“好东西”。

Sometimes, of course, the market may judge a business to be more valuable than the underlying facts would indicate it is. In such a case, we will sell our holdings. Sometimes, also, we will sell a security that is fairly valued or even undervalued because we require funds for a still more undervalued investment or one we believe we understand better.

当然,有时市场也可能把一家企业的价值估得高于事实所能支持的水平。遇到这种情况,我们会卖出持股。有时我们也会卖出一只“估值公允”甚至“被低估”的证券,因为我们需要资金去买一项更被低估的投资,或者买一项我们认为自己理解得更透的投资。

We need to emphasize, however, that we do not sell holdings just because they have appreciated or because we have held them for a long time. (Of Wall Street maxims the most foolish may be “You can’t go broke taking a profit.”) We are quite content to hold any security indefinitely, so long as the prospective return on equity capital of the underlying business is satisfactory, management is competent and honest, and the market does not overvalue the business.

但我们需要强调:我们不会仅仅因为持股上涨了,或因为持股时间很长,就去卖出。(在华尔街格言里,最蠢的也许就是:“落袋为安永远不会破产。”)只要标的企业对权益资本的预期回报令人满意、管理层既能干又诚实、且市场没有把企业估得过高,我们就完全乐意无限期持有任何证券。

However, our insurance companies own three marketable common stocks that we would not sell even though they became far overpriced in the market. In effect, we view these investments exactly like our successful controlled businesses—a permanent part of Berkshire rather than merchandise to be disposed of once Mr. Market offers us a sufficiently high price. To that, I will add one qualifier: These stocks are held by our insurance companies and we would, if absolutely necessary, sell portions of our holdings to pay extraordinary insurance losses. We intend, however, to manage our affairs so that sales are never required.

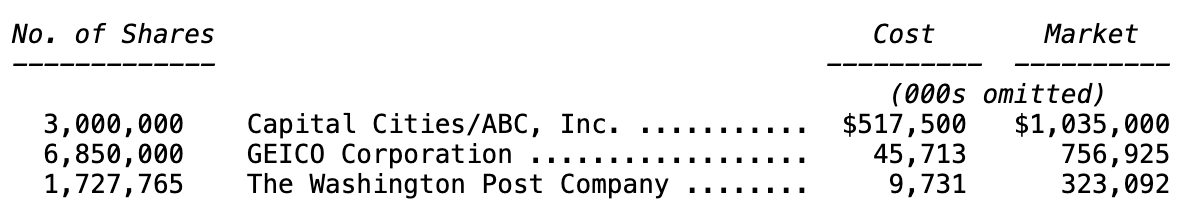

不过,我们的保险公司持有三只可交易普通股:即便它们在市场上被严重高估,我们也不会卖出。实质上,我们把这些投资看得和我们那些成功的控股企业完全一样——它们是 Berkshire 的永久组成部分,而不是一旦 Mr. Market 报出足够高价格就要处理掉的“货物”。我还要补充一个限定:这些股票由我们的保险公司持有;如果真的到了绝对必要的时候,我们会卖出一部分持仓来支付异常巨大的保险赔付损失。但我们的意图是把事情管理好,使得这种卖出永远不需要发生。

A determination to have and to hold, which Charlie and I share, obviously involves a mixture of personal and financial considerations. To some, our stand may seem highly eccentric. (Charlie and I have long followed David Oglivy’s advice: “Develop your eccentricities while you are young. That way, when you get old, people won’t think you’re going ga-ga.”) Certainly, in the transaction-fixated Wall Street of recent years, our posture must seem odd: To many in that arena, both companies and stocks are seen only as raw material for trades.

这种“立志持有、并长期持有”的决心——Charlie 和我都认同——显然混合了个人因素与财务因素。在一些人看来,我们的立场可能非常古怪。(Charlie 和我长期遵循 David Ogilvy 的建议:“趁年轻把你的怪癖培养出来。这样等你老了,人们也不会以为你变傻了。”)当然,在近些年那个痴迷交易的华尔街里,我们的姿态必然显得反常:对那里的许多人而言,公司与股票只是交易的原材料。

个人因素:不想处理让人烦心的人事,以及由此导致的紧张氛围;财务因素:忠诚带来的积极因素,包括安全感。

Our attitude, however, fits our personalities and the way we want to live our lives. Churchill once said, “You shape your houses and then they shape you.” We know the manner in which we wish to be shaped. For that reason, we would rather achieve a return of X while associating with people whom we strongly like and admire than realize 110% of X by exchanging these relationships for uninteresting or unpleasant ones. And we will never find people we like and admire more than some of the main participants at the three companies—our permanent holdings—shown below:

但我们的态度符合我们的性格,也符合我们想要的生活方式。Churchill 曾说:“你塑造你的房子,然后房子也塑造你。”我们知道自己希望被塑造成什么样的人。因此,我们宁愿在与那些我们强烈喜欢并钦佩的人相处的同时,获得 X 的回报,也不愿为了得到 110% 的 X 而把这些关系换成无趣或令人不快的关系。而在下面这三家公司——我们永久持有的投资——中,我们永远找不到比其中一些主要参与者更让我们喜欢与钦佩的人了:

We really don’t see many fundamental differences between the purchase of a controlled business and the purchase of marketable holdings such as these. In each case we try to buy into businesses with favorable long-term economics. Our goal is to find an outstanding business at a sensible price, not a mediocre business at a bargain price. Charlie and I have found that making silk purses out of silk is the best that we can do; with sow’s ears, we fail.

我们确实看不出:收购一家控股企业,和购买像这些一样的可流通持股之间,有多少根本差异。两种情况下,我们都试图买入那些长期经济特性良好的企业。我们的目标是:以合理价格买到卓越企业,而不是以“便宜价”买到平庸企业。Charlie 和我发现:把“丝绸”做成“丝绸钱包”,是我们能做到的最好结果;至于“猪耳朵”,我们总是做不好。

(It must be noted that your Chairman, always a quick study, required only 20 years to recognize how important it was to buy good businesses. In the interim, I searched for “bargains”—and had the misfortune to find some. My punishment was an education in the economics of short-line farm implement manufacturers, third-place department stores, and New England textile manufacturers.)

(必须指出:你们的董事长学习能力很强,但也花了整整20年才认识到“买好企业”有多重要。在那之前,我一直在寻找“便宜货”——不幸的是,还真让我找到了几次。我的惩罚就是:被迫接受一场关于短线农机制造商、排第三的百货商店、以及新英格兰纺织制造商经济学的教育。)

Of course, Charlie and I may misread the fundamental economics of a business. When that happens, we will encounter problems whether that business is a wholly-owned subsidiary or a marketable security, although it is usually far easier to exit from the latter. (Indeed, businesses can be misread: Witness the European reporter who, after being sent to this country to profile Andrew Carnegie, cabled his editor, “My God, you’ll never believe the sort of money there is in running libraries.”)

当然,Charlie 和我也可能误判一家企业的根本经济特性。一旦发生这种情况,无论那家企业是全资子公司还是可交易证券,我们都会遇到麻烦——只不过从后者退出通常容易得多。(企业确实可能被误读:就像那位欧洲记者,被派来美国为 Andrew Carnegie 写人物特写;他给编辑发电报说:“天哪,你绝不会相信经营图书馆竟然有这么多钱。”)

In making both control purchases and stock purchases, we try to buy not only good businesses, but ones run by high-grade, talented and likeable managers. If we make a mistake about the managers we link up with, the controlled company offers a certain advantage because we have the power to effect change. In practice, however, this advantage is somewhat illusory: Management changes, like marital changes, are painful, time-consuming and chancy. In any event, at our three marketable-but permanent holdings, this point is moot: With Tom Murphy and Dan Burke at Cap Cities, Bill Snyder and Lou Simpson at GEICO, and Kay Graham and Dick Simmons at The Washington Post, we simply couldn’t be in better hands.

无论是做控股收购还是买入股票,我们都力求不仅买好企业,还要买那些由高素质、有才华、而且可亲的管理者经营的企业。如果我们在“与谁结盟”这件事上看走了眼,控股公司有一个表面上的优势:我们有权力推动变革。但在实践中,这个优势多少有点“虚幻”:更换管理层就像更换婚姻一样——痛苦、耗时、而且充满不确定性。无论如何,在我们那三项“可交易但永久持有”的投资上,这一点根本不构成问题:Cap Cities 有 Tom Murphy 和 Dan Burke,GEICO 有 Bill Snyder 和 Lou Simpson,The Washington Post 有 Kay Graham 和 Dick Simmons——我们不可能处在更好的托付之下。

I would say that the controlled company offers two main advantages. First, when we control a company we get to allocate capital, whereas we are likely to have little or nothing to say about this process with marketable holdings. This point can be important because the heads of many companies are not skilled in capital allocation. Their inadequacy is not surprising. Most bosses rise to the top because they have excelled in an area such as marketing, production, engineering, administration or, sometimes, institutional politics.

我会说,控股公司有两项主要优势。第一,当我们控股一家企业时,我们可以进行资本配置;而在可交易持股中,我们很可能对资本配置几乎没有发言权。这一点很重要,因为很多公司的负责人并不擅长资本配置。他们的不擅长并不奇怪:多数老板之所以爬到顶端,是因为他们在某个领域表现出色,比如市场营销、生产、工程、行政管理——有时甚至是机构政治。

局部泛化的缺陷,或者说不能产生更简洁、更统一的知识结构终归是有麻烦的,不能有效保存已经到手的胜利果实。

Once they become CEOs, they face new responsibilities. They now must make capital allocation decisions, a critical job that they may have never tackled and that is not easily mastered. To stretch the point, it’s as if the final step for a highly-talented musician was not to perform at Carnegie Hall but, instead, to be named Chairman of the Federal Reserve.

一旦他们成为 CEO,就要面对新的责任:他们必须做资本配置决策——这是一项关键工作,可能是他们从未真正处理过、而且也不容易掌握的工作。把话说得夸张一点:就好像一个极有天赋的音乐家,职业生涯的最后一步不是在 Carnegie Hall 演出,而是被任命为美联储主席。

The lack of skill that many CEOs have at capital allocation is no small matter: After ten years on the job, a CEO whose company annually retains earnings equal to 10% of net worth will have been responsible for the deployment of more than 60% of all the capital at work in the business.

许多 CEO 在资本配置上的欠缺,绝不是小事:在任十年后,如果一家公司每年留存的利润相当于净资产的10%,那么这位 CEO 其实已经对公司运用的全部资本中超过60%的那部分资本的“去向”负过责任了。

CEOs who recognize their lack of capital-allocation skills (which not all do) will often try to compensate by turning to their staffs, management consultants, or investment bankers. Charlie and I have frequently observed the consequences of such “help.” On balance, we feel it is more likely to accentuate the capital-allocation problem than to solve it.

那些意识到自己不擅长资本配置的 CEO(并不是人人都意识到)往往会试图用“求助”来弥补:转向内部幕僚、管理咨询公司或投资银行。Charlie 和我经常观察到这种“帮助”带来的后果。总体上,我们觉得:它更可能放大资本配置的问题,而不是解决问题。

In the end, plenty of unintelligent capital allocation takes place in corporate America. (That’s why you hear so much about “restructuring.”) Berkshire, however, has been fortunate. At the companies that are our major non-controlled holdings, capital has generally been well-deployed and, in some cases, brilliantly so.

归根结底,美国企业界发生了大量不聪明的资本配置。(这就是为什么你总听到那么多“重组”。)不过,Berkshire 很幸运。在我们那些重要的非控股持股公司里,资本总体上被配置得很好,有些情况下甚至堪称精彩。

The second advantage of a controlled company over a marketable security has to do with taxes. Berkshire, as a corporate holder, absorbs some significant tax costs through the ownership of partial positions that we do not when our ownership is 80%, or greater. Such tax disadvantages have long been with us, but changes in the tax code caused them to increase significantly during the past year. As a consequence, a given business result can now deliver Berkshire financial results that are as much as 50% better if they come from an 80%-or-greater holding rather than from a lesser holding.

控股公司相对于可交易证券的第二个优势,与税收有关。作为公司股东,Berkshire 持有非控股(即持股低于80%)的股权时,会承担一些显著的税负成本;而当我们的持股达到或超过80%时,就不会承受这些成本(或会大幅减轻)。这种税收劣势早就存在,但税法的变化使它在过去一年显著加重。因此,同样的经营成果,如果来自持股80%或以上的控股企业,而不是来自较小持股的企业,如今可能给 Berkshire 带来高出多达50%的财务结果。

80%以上的控股没有股息税但还是有资本利得税;如果是外国公司持股,股息有预扣税但没有资本利得税。

The disadvantages of owning marketable securities are sometimes offset by a huge advantage: Occasionally the stock market offers us the chance to buy non-controlling pieces of extraordinary businesses at truly ridiculous prices—dramatically below those commanded in negotiated transactions that transfer control. For example, we purchased our Washington Post stock in 1973 at $5.63 per share, and per-share operating earnings in 1987 after taxes were $10.30. Similarly, Our GEICO stock was purchased in 1976, 1979 and 1980 at an average of $6.67 per share, and after-tax operating earnings per share last year were $9.01. In cases such as these, Mr. Market has proven to be a mighty good friend.

持有可流通证券的劣势,有时会被一个巨大的优势抵消:股市偶尔会给我们机会,让我们以荒谬的价格买到非控股的、极其卓越企业的一部分——价格大幅低于通过谈判交易获得控制权时所需要支付的价格。比如,我们在1973年以每股5.63美元买入 Washington Post;而该公司1987年每股税后经营利润是10.30美元。同样,我们的 GEICO 股票在1976、1979和1980年买入,平均成本为每股6.67美元;而该公司去年每股税后经营利润是9.01美元。在这样的案例里,Mr. Market 的确证明了自己是个非常好的朋友。

An interesting accounting irony overlays a comparison of the reported financial results of our controlled companies with those of the permanent minority holdings listed above. As you can see, those three stocks have a market value of over $2 billion. Yet they produced only $11 million in reported after-tax earnings for Berkshire in 1987.

把我们控股公司与上面列出的三项“永久少数股权”相比,还有一个有趣的会计讽刺叠加在其中。你会看到,这三只股票的市值超过20亿美元;但它们在1987年只给 Berkshire 贡献了1,100万美元的“报告税后收益”。

Accounting rules dictate that we take into income only the dividends these companies pay us—which are little more than nominal—rather than our share of their earnings, which in 1987 amounted to well over $100 million. On the other hand, accounting rules provide that the carrying value of these three holdings—owned, as they are, by insurance companies—must be recorded on our balance sheet at current market prices. The result: GAAP accounting lets us reflect in our net worth the up-to-date underlying values of the businesses we partially own, but does not let us reflect their underlying earnings in our income account.

会计规则要求:我们只能把这些公司支付给我们的股息计入收益——而这些股息几乎只是象征性的——而不能把我们按持股比例应得的利润份额计入收益;而我们按比例应得的那部分利润,在1987年合计远超过1亿美元。另一方面,会计规则又规定:由于这三项持股由保险公司持有,它们在资产负债表上的账面价值必须按当前市场价格记录。结果就是:GAAP 会计允许我们在净资产(net worth)里体现我们部分拥有的企业的“最新底层价值”,却不允许我们在利润表里体现它们的“底层盈利”。

In the case of our controlled companies, just the opposite is true. Here, we show full earnings in our income account but never change asset values on our balance sheet, no matter how much the value of a business might have increased since we purchased it.

对我们的控股公司而言,情况恰恰相反:我们在利润表里体现全部盈利,但资产负债表上的资产价值却永远不调整——无论企业价值在我们买入后上涨了多少。

Our mental approach to this accounting schizophrenia is to ignore GAAP figures and to focus solely on the future earning power of both our controlled and non-controlled businesses. Using this approach, we establish our own ideas of business value, keeping these independent from both the accounting values shown on our books for controlled companies and the values placed by a sometimes foolish market on our partially-owned companies. It is this business value that we hope to increase at a reasonable (or, preferably, unreasonable) rate in the years ahead.

面对这种会计“精神分裂”,我们的心理处理方式是:忽略 GAAP 数字,只关注我们控股与非控股业务未来的盈利能力。用这种方式,我们形成自己对企业价值的判断:既不受控股公司账面会计价值的束缚,也不被市场在我们部分持有公司上偶尔做出的愚蠢定价所左右。我们希望在未来岁月里,以一个合理的(或者更好是“不合理”的)速度提升这种企业价值。

Marketable Securities—Other

可流通证券——其他

In addition to our three permanent common stock holdings, we hold large quantities of marketable securities in our insurance companies. In selecting these, we can choose among five major categories: (1) long-term common stock investments, (2) medium-term fixed-income securities, (3) long-term fixed income securities, (4) short-term cash equivalents, and (5) short-term arbitrage commitments.

除了我们那三项“永久持有”的普通股投资外,我们在保险公司里还持有大量可流通证券。在选择这些证券时,我们可以在五大类别中做取舍:(1) 长期普通股投资;(2) 中期固定收益证券;(3) 长期固定收益证券;(4) 短期现金等价物;(5) 短期套利承诺。

We have no particular bias when it comes to choosing from these categories. We just continuously search among them for the highest after-tax returns as measured by “mathematical expectation,” limiting ourselves always to investment alternatives we think we understand. Our criteria have nothing to do with maximizing immediately reportable earnings; our goal, rather, is to maximize eventual net worth.

在这几类之间做选择时,我们并没有特定偏好。我们只是持续在它们之间寻找“以数学期望衡量”的最高税后回报,同时始终把自己限制在那些我们认为自己能理解的投资选择之内。我们的标准与最大化当期可报告利润毫无关系;相反,我们的目标是最大化最终净资产(net worth)。

资产负债表,过去10年、20年合计赚了多少钱。

Let’s look first at common stocks. During 1987 the stock market was an area of much excitement but little net movement: The Dow advanced 2.3% for the year. You are aware, of course, of the roller coaster ride that produced this minor change. Mr. Market was on a manic rampage until October and then experienced a sudden, massive seizure.

先看普通股。1987年,股市是一个“令人兴奋但净变化不大”的领域:道指全年上涨2.3%。当然,你也知道,正是那场过山车式的剧烈波动,才最终只留下这么一点点变化。Mr. Market 在10月之前处于躁狂式狂奔,随后又突然、剧烈地抽搐发作。

We have “professional” investors, those who manage many billions, to thank for most of this turmoil. Instead of focusing on what businesses will do in the years ahead, many prestigious money managers now focus on what they expect other money managers to do in the days ahead. For them, stocks are merely tokens in a game, like the thimble and flatiron in Monopoly.

这场动荡,大部分要“感谢”那些管理着数以百亿计资金的“职业”投资者。许多声望很高的资金经理,如今不再关注企业未来几年会做出什么,而是关注他们预期“其他资金经理未来几天会做什么”。在他们眼里,股票只是游戏里的筹码,就像《大富翁》里的顶针和熨斗。

An extreme example of what their attitude leads to is “portfolio insurance,” a money-management strategy that many leading investment advisors embraced in 1986-1987. This strategy—which is simply an exotically-labeled version of the small speculator’s stop-loss order dictates that ever increasing portions of a stock portfolio, or their index-future equivalents, be sold as prices decline. The strategy says nothing else matters: A downtick of a given magnitude automatically produces a huge sell order. According to the Brady Report, $60 billion to $90 billion of equities were poised on this hair trigger in mid-October of 1987.

这种心态导致的一个极端例子,是“portfolio insurance(投资组合保险)”——一种在1986-1987年被许多头部投资顾问追捧的资金管理策略。这种策略——说到底,不过是给小散户的“止损单”披上了一个更花哨的名字——要求:随着价格下跌,必须卖出越来越大比例的股票组合(或其股指期货等价物)。策略宣称其他一切都不重要:只要价格出现某个幅度的下跳,就自动触发一笔巨大的卖单。按照 Brady Report 的说法,1987年10月中旬,有600亿到900亿美元的股票,就这样处在这种“发丝扳机”之上。

If you’ve thought that investment advisors were hired to invest, you may be bewildered by this technique. After buying a farm, would a rational owner next order his real estate agent to start selling off pieces of it whenever a neighboring property was sold at a lower price? Or would you sell your house to whatever bidder was available at 9:31 on some morning merely because at 9:30 a similar house sold for less than it would have brought on the previous day?

如果你一直以为投资顾问是被雇来“投资”的,那么这套技术可能会让你困惑:一个理性的人买下一座农场后,会不会接着就命令他的房产中介——只要邻近地块以更低价格成交,就立刻卖掉自己农场的一部分?或者,你会不会仅仅因为9:30有一栋类似房子以更低价格成交,就在某个早晨的9:31把自己的房子按当时能拿到的任何出价卖掉?

Moves like that, however, are what portfolio insurance tells a pension fund or university to make when it owns a portion of enterprises such as Ford or General Electric. The less these companies are being valued at, says this approach, the more vigorously they should be sold. As a “logical” corollary, the approach commands the institutions to repurchase these companies—I’m not making this up—once their prices have rebounded significantly. Considering that huge sums are controlled by managers following such Alice-in-Wonderland practices, is it any surprise that markets sometimes behave in aberrational fashion?

但“投资组合保险”正是要求养老金或大学基金在持有 Ford 或 General Electric 这类企业的一部分时,做出类似举动。这种方法说:企业估值越低,就越应该更积极地卖出。作为一个“逻辑上的”推论,它还命令机构在这些企业价格显著反弹后再把它们买回来——我没有编造。考虑到如此巨额的资金被遵循这种《爱丽丝梦游仙境》式做法的经理人所掌控,市场有时出现反常行为,又有什么好奇怪的呢?

Many commentators, however, have drawn an incorrect conclusion upon observing recent events: They are fond of saying that the small investor has no chance in a market now dominated by the erratic behavior of the big boys. This conclusion is dead wrong: Such markets are ideal for any investor—small or large—so long as he sticks to his investment knitting. Volatility caused by money managers who speculate irrationally with huge sums will offer the true investor more chances to make intelligent investment moves. He can be hurt by such volatility only if he is forced, by either financial or psychological pressures, to sell at untoward times.

不过,很多评论员在观察到近期事件后得出了一个错误结论:他们喜欢说,在一个如今被“大机构”反复无常行为所主导的市场里,小投资者没有任何机会。这个结论大错特错:只要投资者(无论大小)坚持做自己该做的那一类投资,这样的市场反而是理想的。由资金经理用巨额资金进行非理性投机所引发的波动,会给真正的投资者更多机会去做出理性的投资决策。只有在他因为财务压力或心理压力被迫在不合时宜的时候卖出时,这种波动才会伤害到他。

At Berkshire, we have found little to do in stocks during the past few years. During the break in October, a few stocks fell to prices that interested us, but we were unable to make meaningful purchases before they rebounded. At yearend 1987 we had no major common stock investments (that is, over $50 million) other than those we consider permanent or arbitrage holdings. However, Mr. Market will offer us opportunities—you can be sure of that—and, when he does, we will be willing and able to participate.

在 Berkshire,过去几年我们在股票上几乎没什么可做。10月那次暴跌期间,有少数股票跌到了让我们感兴趣的价格,但我们没能在它们反弹之前完成有意义的买入。截至1987年年底,除我们视为永久持有或套利持有的股票外,我们没有任何重大的普通股投资(即单项超过5,000万美元)。不过,Mr. Market 一定还会给我们机会——你尽可以放心——而当他这么做时,我们也将既愿意、也有能力参与。

In the meantime, our major parking place for money is medium-term tax-exempt bonds, whose limited virtues I explained in last year’s annual report. Though we both bought and sold some of these bonds in 1987, our position changed little overall, holding around $900 million. A large portion of our bonds are “grandfathered” under the Tax Reform Act of 1986, which means they are fully tax-exempt. Bonds currently purchased by insurance companies are not.

与此同时,我们主要的“停车场”是中期免税债券。它们的有限优点,我在去年的年报中已解释过。尽管1987年我们既买也卖了一些这类债券,但总体持仓变化不大,仍在约9亿美元水平。我们债券中很大一部分在《1986年税改法案》下被“grandfathered(旧规豁免)”,这意味着它们完全免税;而保险公司现在新买的债券则不是。

As an alternative to short-term cash equivalents, our medium-term tax-exempts have—so far served us well. They have produced substantial extra income for us and are currently worth a bit above our cost. Regardless of their market price, we are ready to dispose of our bonds whenever something better comes along.

作为短期现金等价物的替代品,我们的中期免税债券——到目前为止——表现不错。它们为我们带来了可观的额外收入,目前市值也略高于成本。无论市场价格如何,只要出现更好的机会,我们随时准备处置这些债券。

We continue to have an aversion to long-term bonds (and may be making a serious mistake by not disliking medium-term bonds as well). Bonds are no better than the currency in which they are denominated, and nothing we have seen in the past year—or past decade—makes us enthusiastic about the long-term future of U.S. currency.

我们仍然厌恶长期债券(而且我们可能犯了一个严重错误:没有同样厌恶中期债券)。债券的好坏不可能超过其计价货币本身的好坏;而在过去一年——甚至过去十年——我们所看到的一切,都没法让我们对美元的长期未来感到兴奋。

Our enormous trade deficit is causing various forms of “claim checks”—U.S. government and corporate bonds, bank deposits, etc.—to pile up in the hands of foreigners at a distressing rate. By default, our government has adopted an approach to its finances patterned on that of Blanche DuBois, of A Streetcar Named Desire, who said, “I have always depended on the kindness of strangers.” In this case, of course, the “strangers” are relying on the integrity of our claim checks although the plunging dollar has already made that proposition expensive for them.

我们巨大的贸易赤字,正在以令人不安的速度把各种形式的“索赔凭证”(claim checks)——美国政府与公司债券、银行存款等——堆到外国人手里。事实上,我们的政府在财政上采取了一种“默认策略”,其模式很像《欲望号街车》里的 Blanche DuBois:她说过,“我一向依靠陌生人的善意。”在这里,所谓“陌生人”,当然就是那些在依赖我们索赔凭证信用的外国人——尽管美元的持续下跌已经让这种依赖对他们来说变得昂贵。

The faith that foreigners are placing in us may be misfounded. When the claim checks outstanding grow sufficiently numerous and when the issuing party can unilaterally determine their purchasing power, the pressure on the issuer to dilute their value by inflating the currency becomes almost irresistible. For the debtor government, the weapon of inflation is the economic equivalent of the “H” bomb, and that is why very few countries have been allowed to swamp the world with debt denominated in their own currency. Our past, relatively good record for fiscal integrity has let us break this rule, but the generosity accorded us is likely to intensify, rather than relieve, the eventual pressure on us to inflate. If we do succumb to that pressure, it won’t be just the foreign holders of our claim checks who will suffer. It will be all of us as well.

外国人对我们的信任,也许并不牢靠。当外部持有的索赔凭证足够多、而发行方又可以单方面决定这些凭证的购买力时,发行方用通货膨胀去稀释其价值的压力就会变得几乎不可抗拒。对负债的政府而言,通胀这件武器在经济上的威力,等同于“氢弹”;也正因此,很少有国家被允许用本国货币计价的债务去“淹没世界”。我们过去相对不错的财政信誉让我们打破了这条规则,但外界给予我们的宽容,很可能会加剧——而不是减轻——未来逼迫我们走向通胀的压力。如果我们最终屈服于这种压力,受伤的不只是那些持有我们索赔凭证的外国人——我们所有人也都会一起受伤。

Of course, the U.S. may take steps to stem our trade deficit well before our position as a net debtor gets out of hand. (In that respect, the falling dollar will help, though unfortunately it will hurt in other ways.) Nevertheless, our government’s behavior in this test of its mettle is apt to be consistent with its Scarlett O’Hara approach generally: “I’ll think about it tomorrow.” And, almost inevitably, procrastination in facing up to fiscal problems will have inflationary consequences. Both the timing and the sweep of those consequences are unpredictable. But our inability to quantify or time the risk does not mean we should ignore it. While recognizing the possibility that we may be wrong and that present interest rates may adequately compensate for the inflationary risk, we retain a general fear of long-term bonds.

当然,美国也可能在“净负债国”的地位失控之前,就采取措施遏制贸易赤字。(在这方面,美元贬值会有帮助,尽管不幸的是它也会以其他方式造成伤害。)尽管如此,我们政府在这场“考验气节”的挑战中,其行为很可能仍会延续它一贯的 Scarlett O’Hara 式风格:“明天再想。”而在财政问题上拖延,几乎不可避免会带来通胀后果。这些后果何时出现、影响有多大,都无法预测。但我们无法量化或把握风险的时间点,并不意味着我们应该忽视风险。即便承认:我们也可能错了、当前利率也许足以补偿通胀风险,我们仍然对长期债券保持总体上的恐惧。

We are, however, willing to invest a moderate portion of our funds in this category if we think we have a significant edge in a specific security. That willingness explains our holdings of the Washington Public Power Supply Systems #1, #2 and #3 issues, discussed in our 1984 report. We added to our WPPSS position during 1987. At yearend, we had holdings with an amortized cost of $240 million and a market value of $316 million, paying us tax-exempt income of $34 million annually.

不过,如果我们认为在某只特定证券上拥有显著优势,我们愿意把一部分资金以“适度比例”配置到这一类别。这种愿意解释了我们持有 Washington Public Power Supply Systems(WPPSS)#1、#2、#3 期债券——我们在1984年报告中讨论过。1987年我们还增加了 WPPSS 的持仓。截至年末,我们持有的债券摊余成本为2.40亿美元,市值为3.16亿美元,每年带来3,400万美元的免税收入。